Few places have such an instant calming effect on my entire being than Grand Teton National Park in Jackson Hole, Wyoming – along with an infectious and constant desire to get out and shoot every morning.

So what better place to take Phase One’s latest Medium Format XT – Rodenstock 40mm Tilt lens out for a spin?

Well, a tilt, at least.

“But when can we get some tilt?”

When the XT field camera originally launched, this was one of the specific requests that headed into Phase One‘s engineers from technical camera users.

The answer?

Now.

Right now – the new 40mm is now shipping – and as expected, it’s quite the piece of precision engineering.

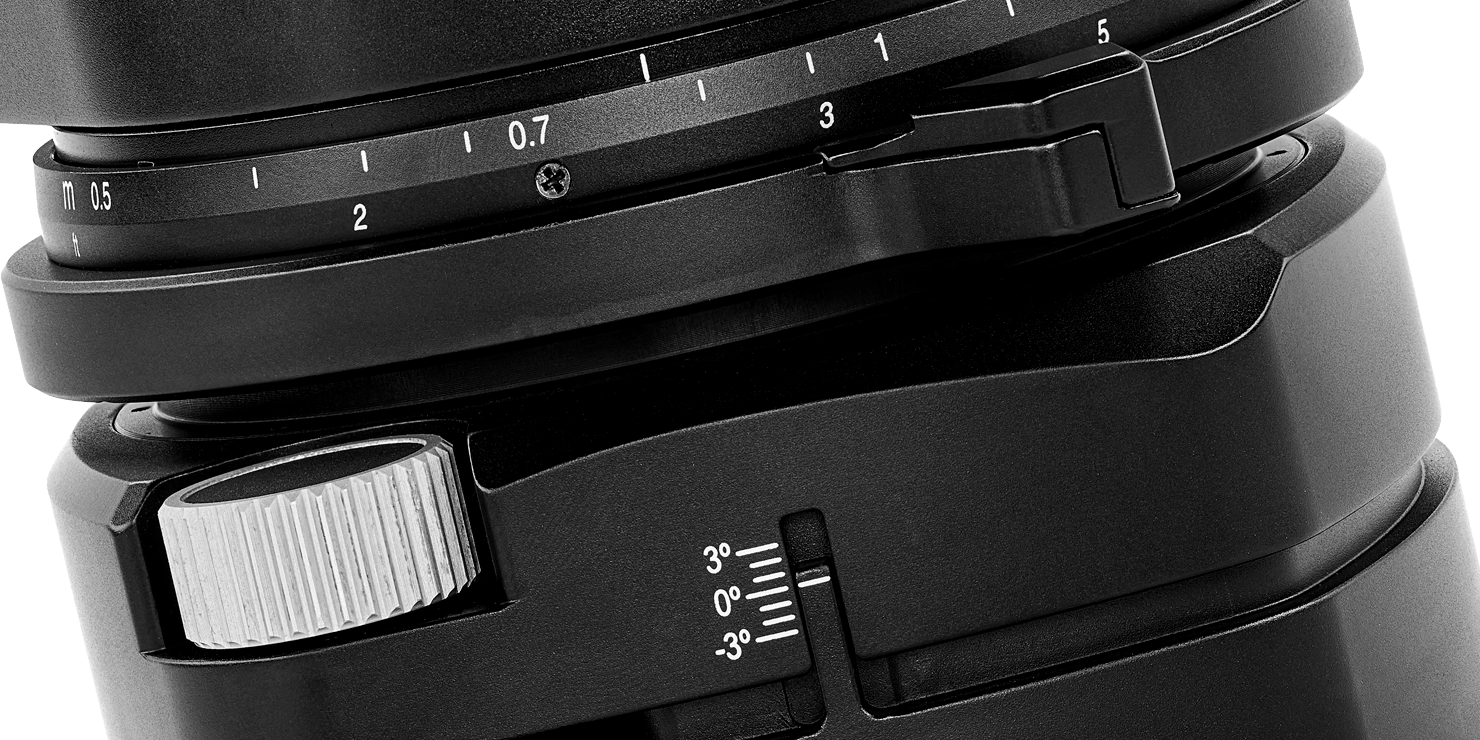

I know from my own calls, I’d been asking for “even just a little bit!” when it came to tilting the lens away from the parallel focal plane of the camera – and the option that Phase One have now delivered is a new compact unit with a single extra dial, allowing for +/- 3º of movement.

“But what’s that for?” – a fair question, and one that many who saw me testing it wanted to know.

To begin the explanation, we need to remember that we already had “shift” on the XT camera (which allows us to correct for perspective distortion, as well as facilitating the stitching of images from side to side with no errors). But it still leaves the focal plane parallel to the sensor itself, and as you’ll soon see – that presents some challenges when shooting certain subjects in the field.

So this isn’t about correcting perspective, this is about altering focus.

My testing ground – Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Landing into Jackson Hole is an awesome experience in itself, well worth the pre-dawn departure from Las Vegas, connecting through Arizona and then finally up north. Over the years I’ve been coming here, I’ll never tire of that view on approach – the incredible Teton mountain range on the one side, balanced by the expansive flats and wildlife refuges to the other – and who doesn’t love a walk outside to/from the plane?

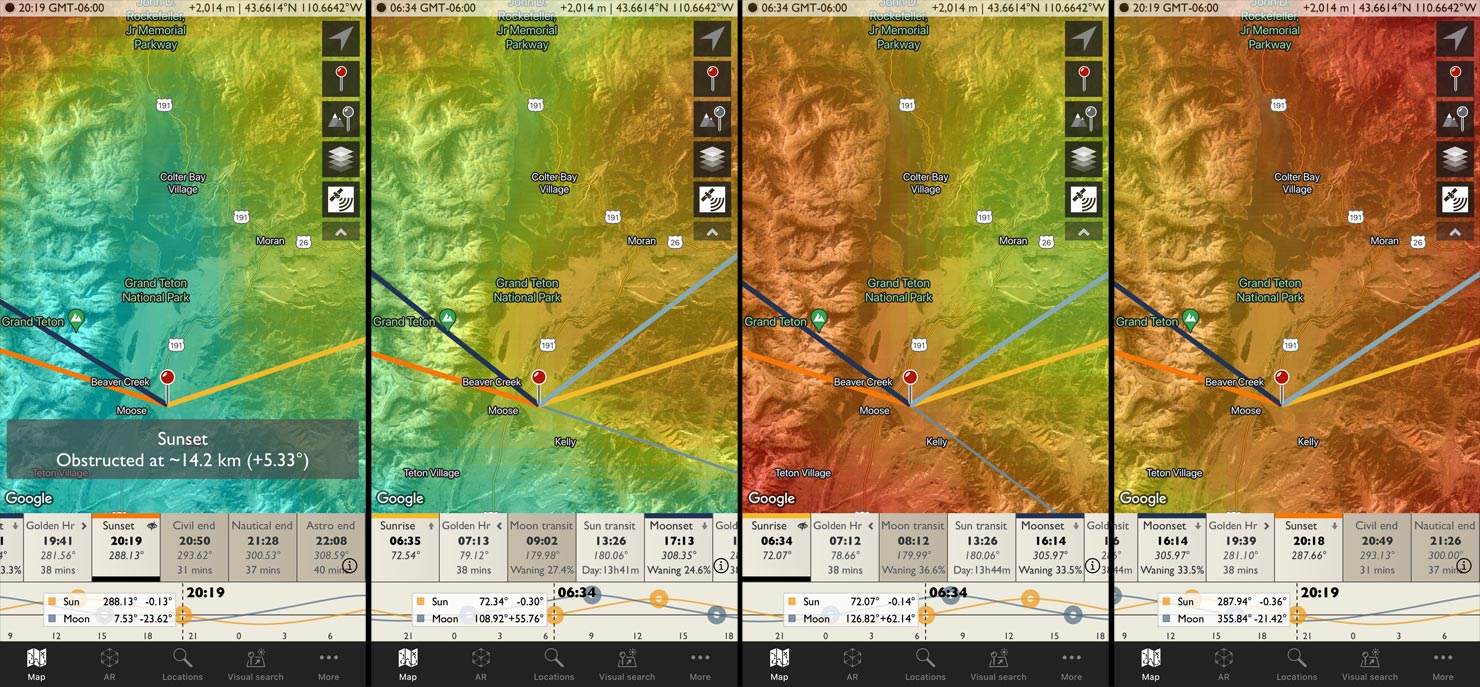

Heading into Grand Teton National Park for sunset and sunrise, I was sure I’d have the perfect conditions to give the new lens a quick test, but the sky stopped just short of co-operating. Furthermore, with the still reflection (at infinity) in the water before me, the use of the tilt lens was hardly going to be put to the test in this, rather classic, postcard landscape shot down by the river.

Still, there was always the future weather to look forward to…

Knowing there would be more “front to back” challenge when shooting next to a large foreground object, I figured the old barns on Mormon Row would make for a much better proving ground, and a change of scenery for this trip too.

I’ve shot these barns on many occasions – and while the view is impressive year-round, you do find yourself shooting at f/16+ when getting up-close, even on a relatively wide (say, 28mm) lens, just to get most of the shot in focus. On a positive, most modern cameras can handle it (and certainly my Phase One XF or XT can), but this would be an ideal proving ground for such a challenge of focal plane.

I reviewed one of my previous shots, and noticed, from studying the raws, that I’d historically had to make a sacrifice:

- Either shoot the barn sharp at around f/8, but lose the detail in the distant mountains, or,

- Shoot soft at f/16-f/22 (gasp!) and compromise overall detail due to diffraction in return for everything appearing in focus.

I’ve always enjoyed shooting Mormon Row, and love some of my older shots here, but it was time to see what could really be captured with an even better tool for the job.

Tilt Lenses – Why focal planes matter.

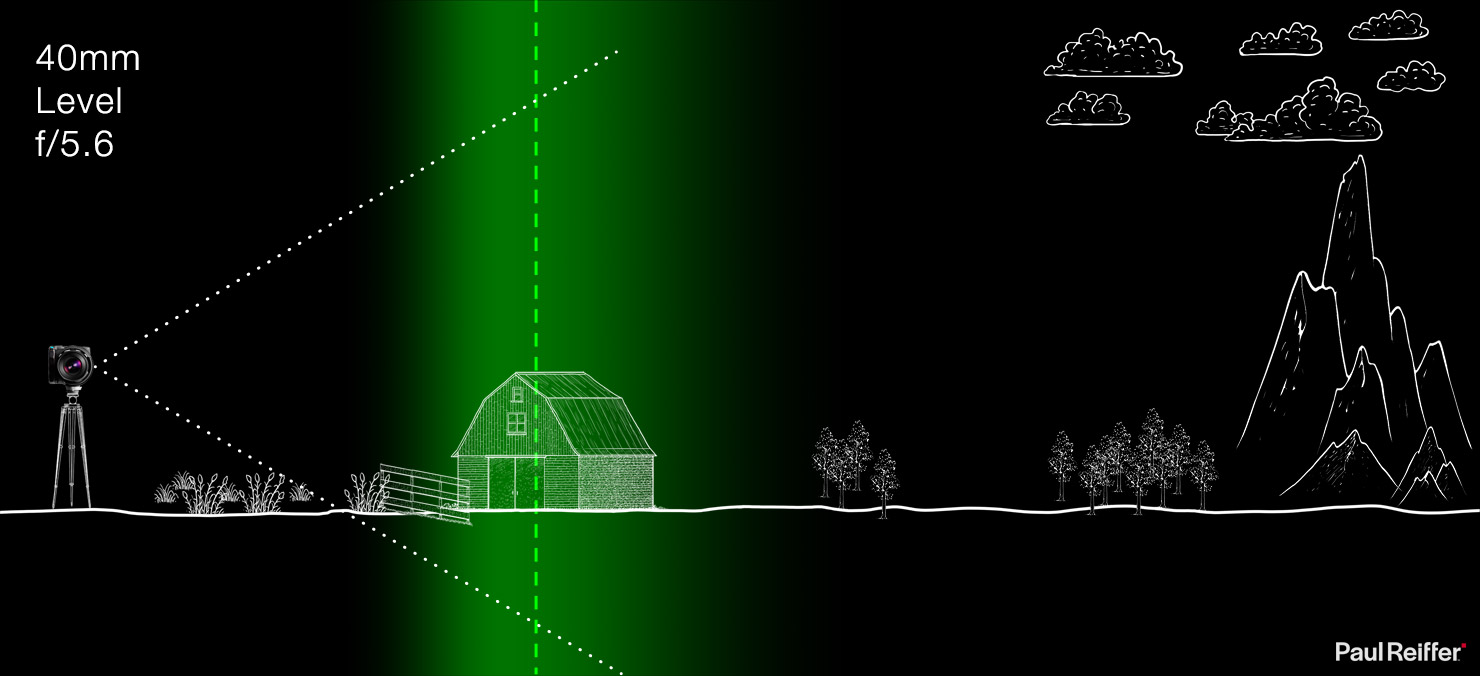

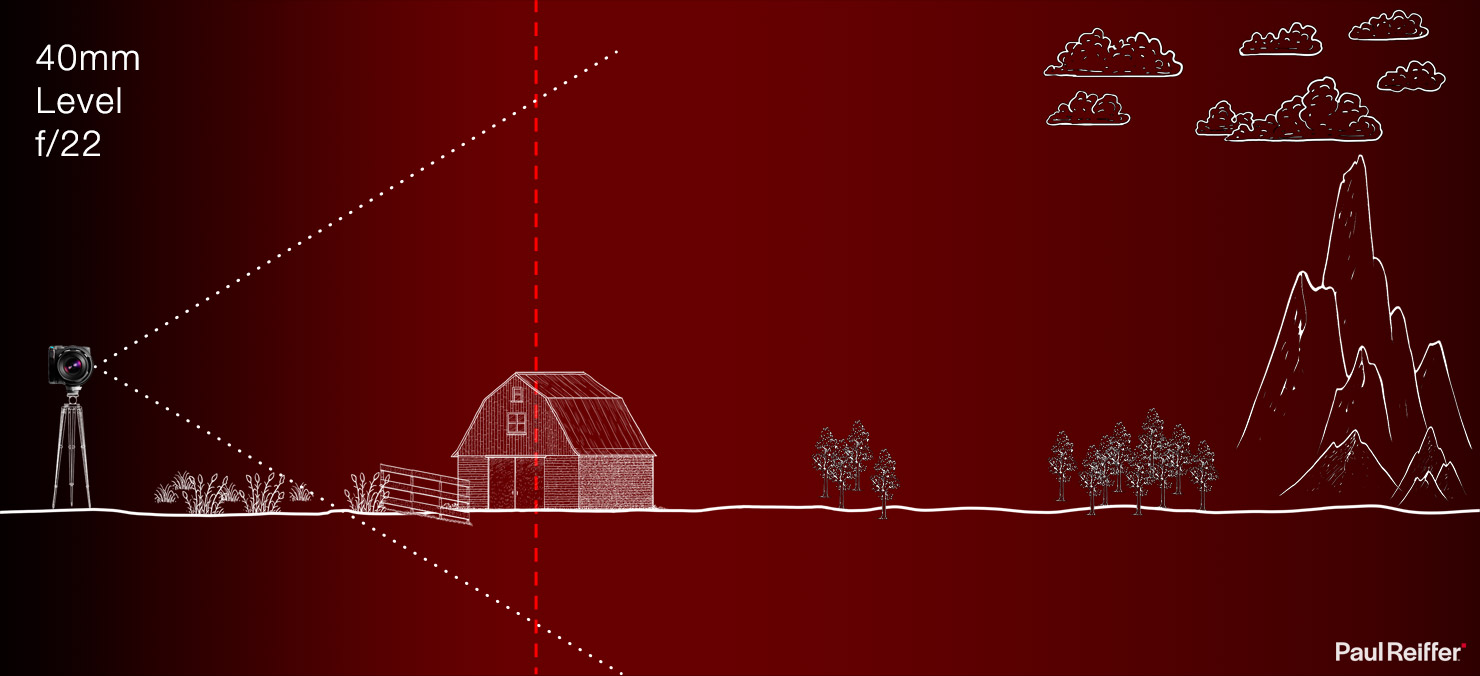

So what’s the issue with a standard lens?

The issue is compromise. You see, whenever we shoot a huge depth of field with a standard lens that’s mounted parallel to the sensor plane, we have to sacrifice something in order to get the result we’re expecting.

Shoot at a wide aperture, such as f/5.6 – and you’ll find the elements that are in the associated “Depth of Field” are tack-sharp, but, most other elements before or after that plane fall into bokeh (the “soft parts” of an image) – or as we’d more commonly call it, “blurry and out of focus”.

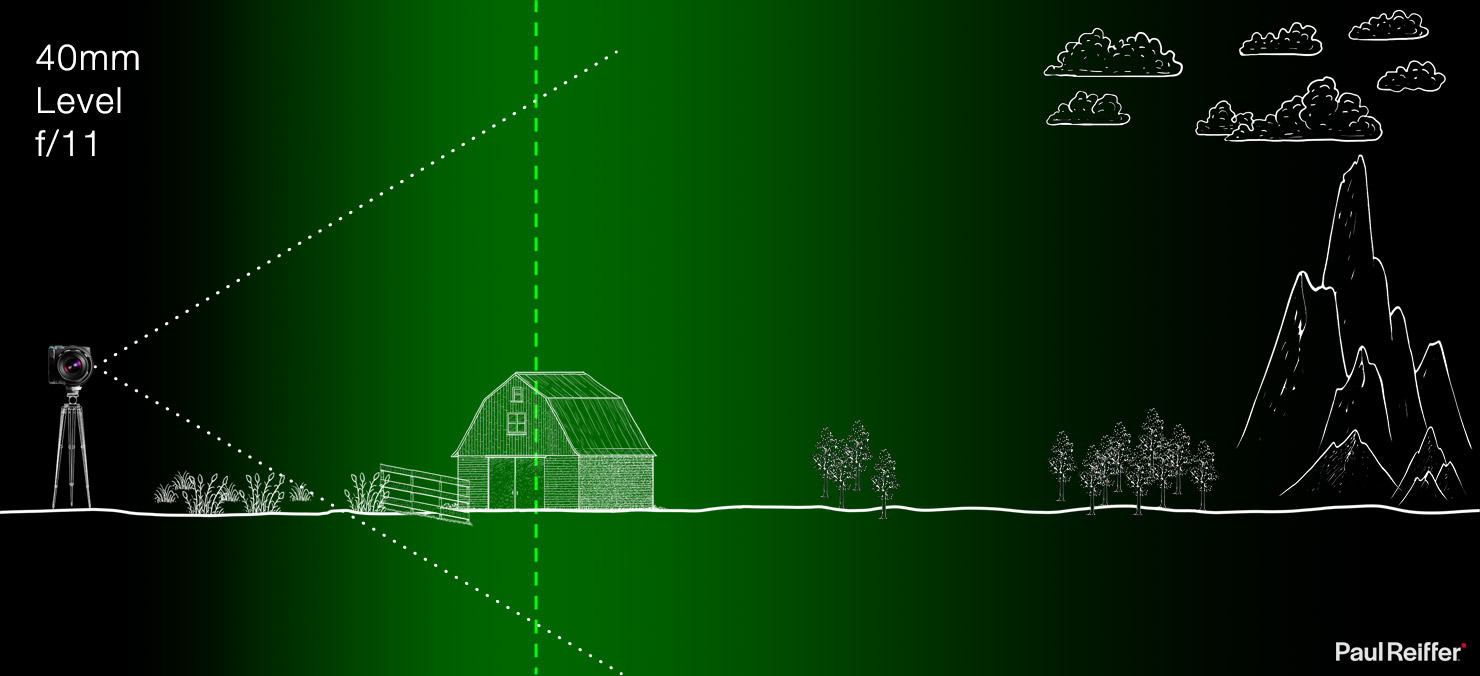

So what if we aim to shoot at a smaller aperture instead, say, f/11?

Well, we certainly grow our depth of field, but when the near subject is so near to us, and the far object is so far away – even that can be a challenge to get all elements nice and sharp.

Take that one further, let’s look at shooting with a really small aperture – what about f/16, f/22?

While our DoF grows substantially (to the point where, yes, everything in the scene appears in focus), we find ourselves facing another challenge with glass optics: heavy diffraction. And that defeats the whole point of us using a smaller aperture to get things sharp in the first place as diffraction softens the details in the image itself.

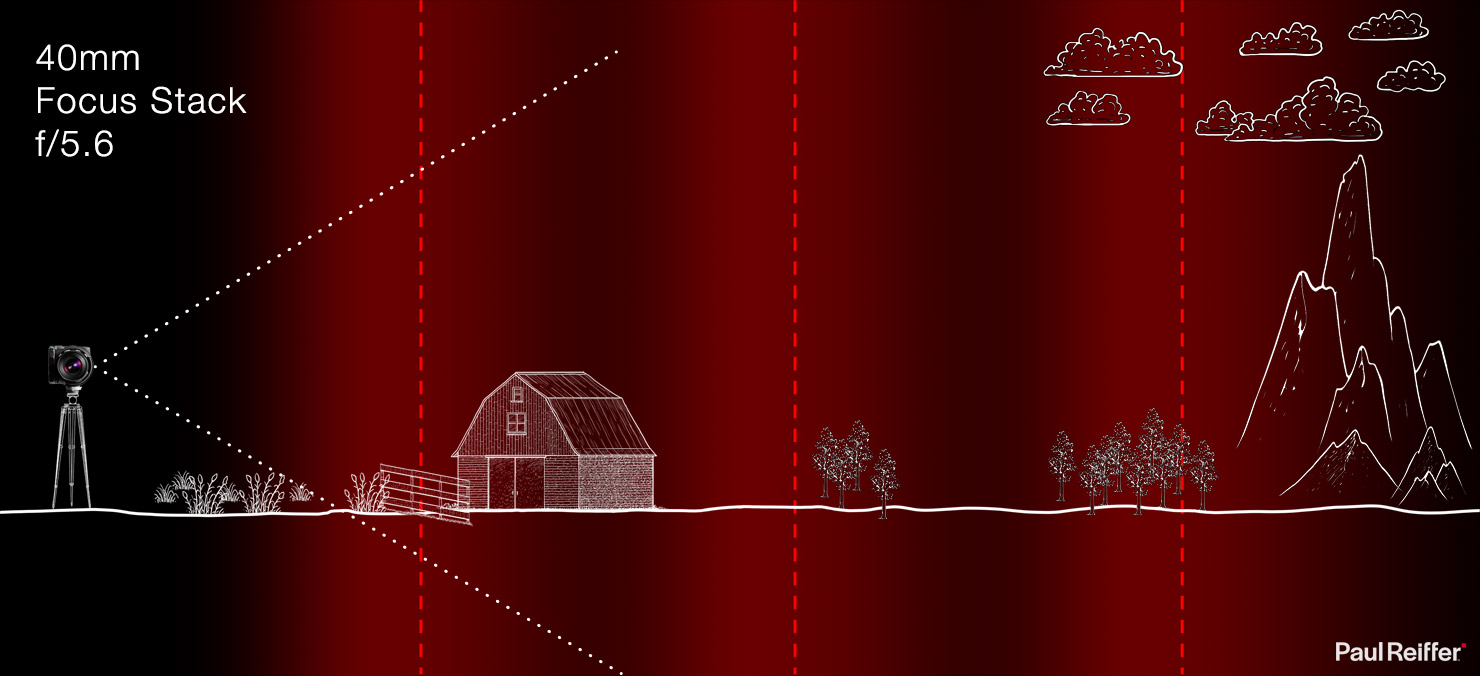

So if our ideal aperture for sharpness is around f/8, what if we took multiple images of the same scene, and moved the focus point throughout from front to back, blending those captures together, later on, in software?

That’s called Focus Stacking – and while, in controlled environments, this can be particularly handy – when objects (like trees, clouds, grass) are moving and/or we want to produce a sweeping long exposure shot, the results from all those joins are invariably a let-down.

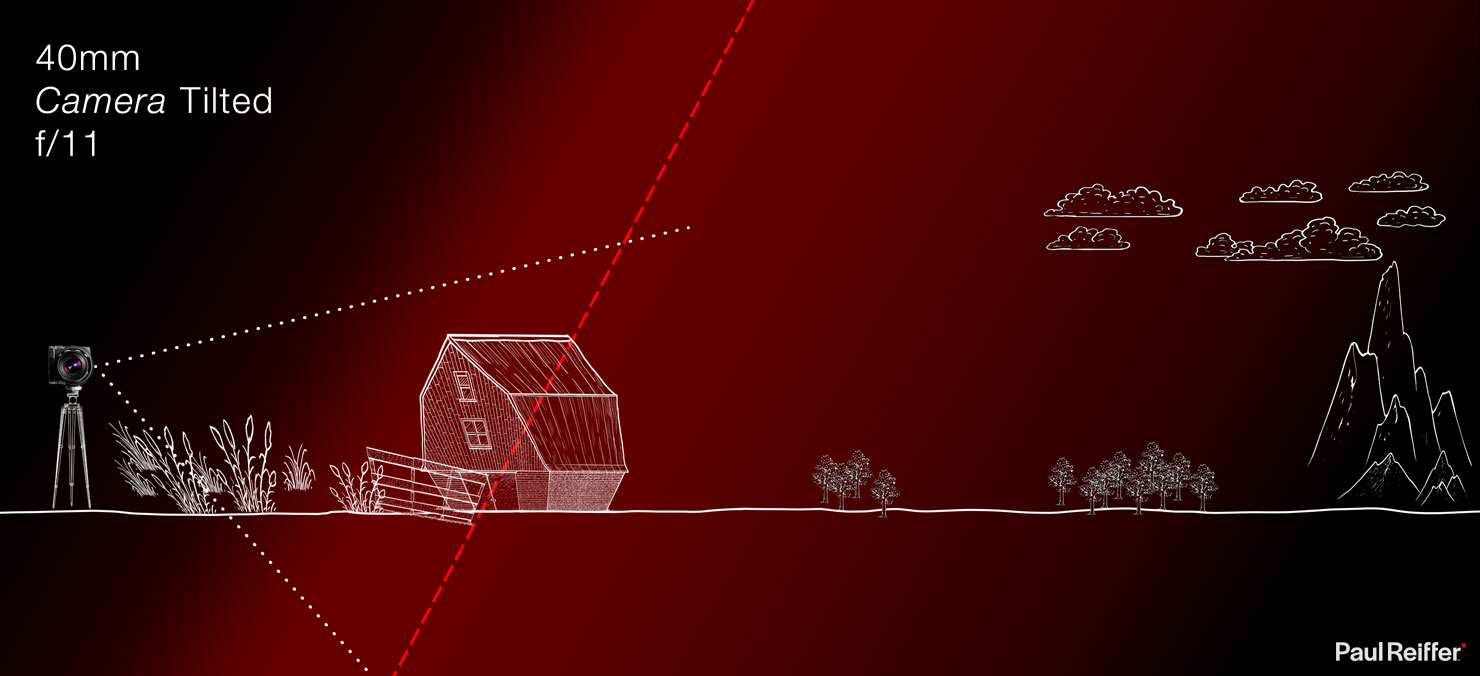

So maybe the answer is to tilt the camera?

We could “throw” the focal plane out, into the distance, using a wide enough aperture for sharpness (but narrow enough to gain the right depth of field) while keeping to our single shot.

Great, right?

Wrong.

You see, the problem with tilting the camera (and therefore the sensor, as well as the lens) is that we change the perspective in which we look at the scene. Close objects bulge, far objects shrink, and the image becomes entirely unnatural. Yes, we can use a bit of “shift” in the lens to compensate for this, but it’s never going to give a truly clean result.

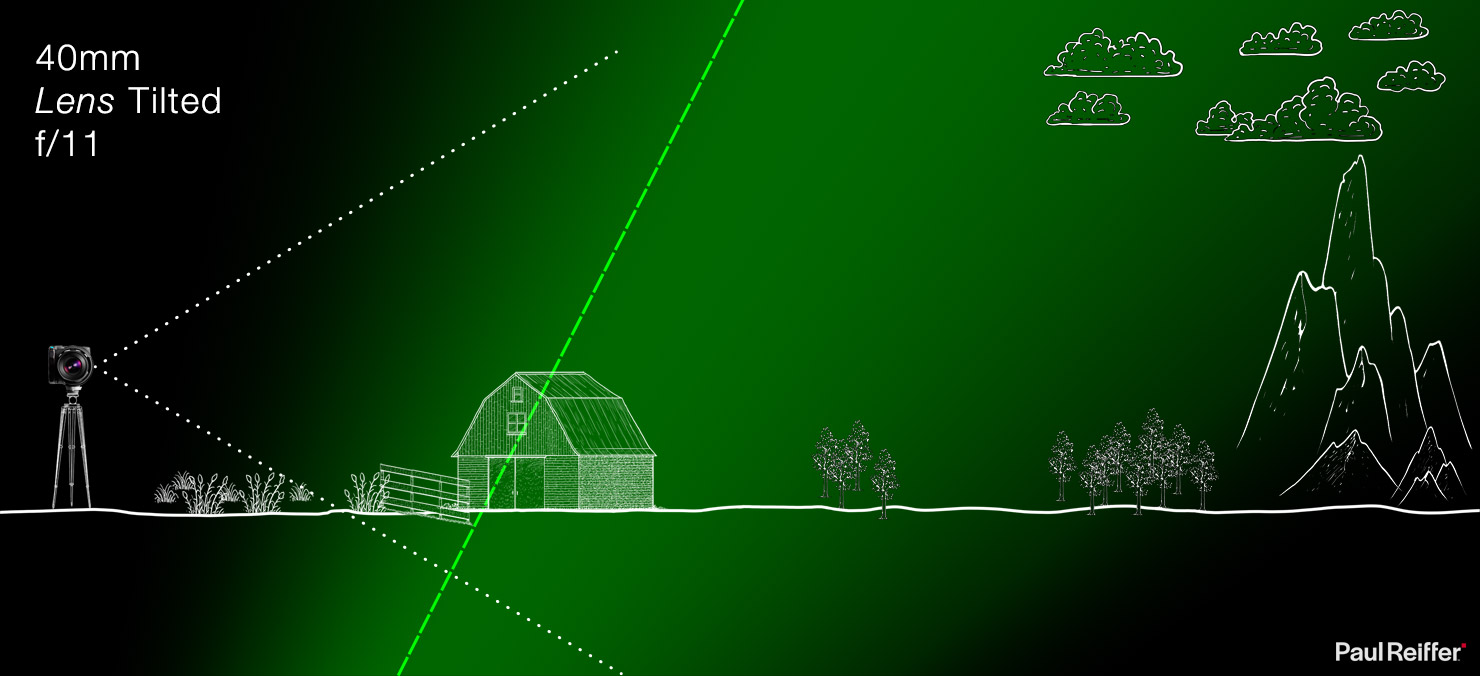

So what if there was a way of throwing the focal plane of the lens out, independently to that of the sensor?

Well, there is – and it’s called a tilt (and in some cases, swing) lens.

By tilting the angle of the lens to be at a different plane to that of the sensor, we actually throw the focal plane out across our scene in a very handy way indeed.

The plane itself doesn’t actually stay parallel from top to bottom (it becomes a kind of “cone”, converging near to the camera) – and something called the Scheimpflug principle comes into play.

The net result?

I can shoot a scene with a much wider (read: sharper) aperture than the scene would normally require, while keeping all elements from near to far in as much (or as little – it works both ways, more on that later) focus as I need.

The 40mm XT Tilt lens in the field

With all that in mind, let’s head back to that wonderfully predicted morning sunrise over the John Moulton Barn and Homestead in Wyoming’s “Mormon Row”.

I used the Phase One IQ4 frame averaging function to avoid the use of any filters, resulting in a 5 minute equivalent exposure as the light on the morning clouds travelled across the frame.

At first glance, this is a regular f/11 shot of a barn that’s near to us with Grand Teton and its neighbours in the background, all in focus.

I mean, I love this shot – and I’d be happy with it on a standard lens too, but look what happens when we zoom in to compare:

The shot on the left is an f/11 shot, focused on the barn, with no tilt on the lens. It’s a standard focal plane, as any standard lens would have, and the result is perfectly fine – but not quite sharp in the distant details of those mountains…

Especially when compared to the shot on the right – which is what happens when we throw the tilt on that lens over by a couple of degrees. Such a small change, but wow – what a huge difference.

Everything in that scene, at exactly the same aperture, is now tack-sharp from front to back.

The Teton mountain range in the distant background – nearly 15km away – is full of incredible details, especially from a 40mm lens that’s theoretically focused only a few metres away.

But so too are the incredible textures in the wood of the ancient barn itself – with nothing left out of focus.

Even the grasses that sit right next to my tripod got their moment in the limelight – for those that weren’t moving in the wind, it’s every single detail that can be seen up-close that makes the difference.

What if we want less in focus?

I mentioned earlier that, due to the same principles, we could also use a tilt-enabled lens to provide less focus to a scene.

Think of those “miniature cities” you’ve seen captured on camera, where it pretends to be taken up-close with a ridiculously wide aperture, when really it was a standard distance away: Those have typically been achieved with a tilt lens.

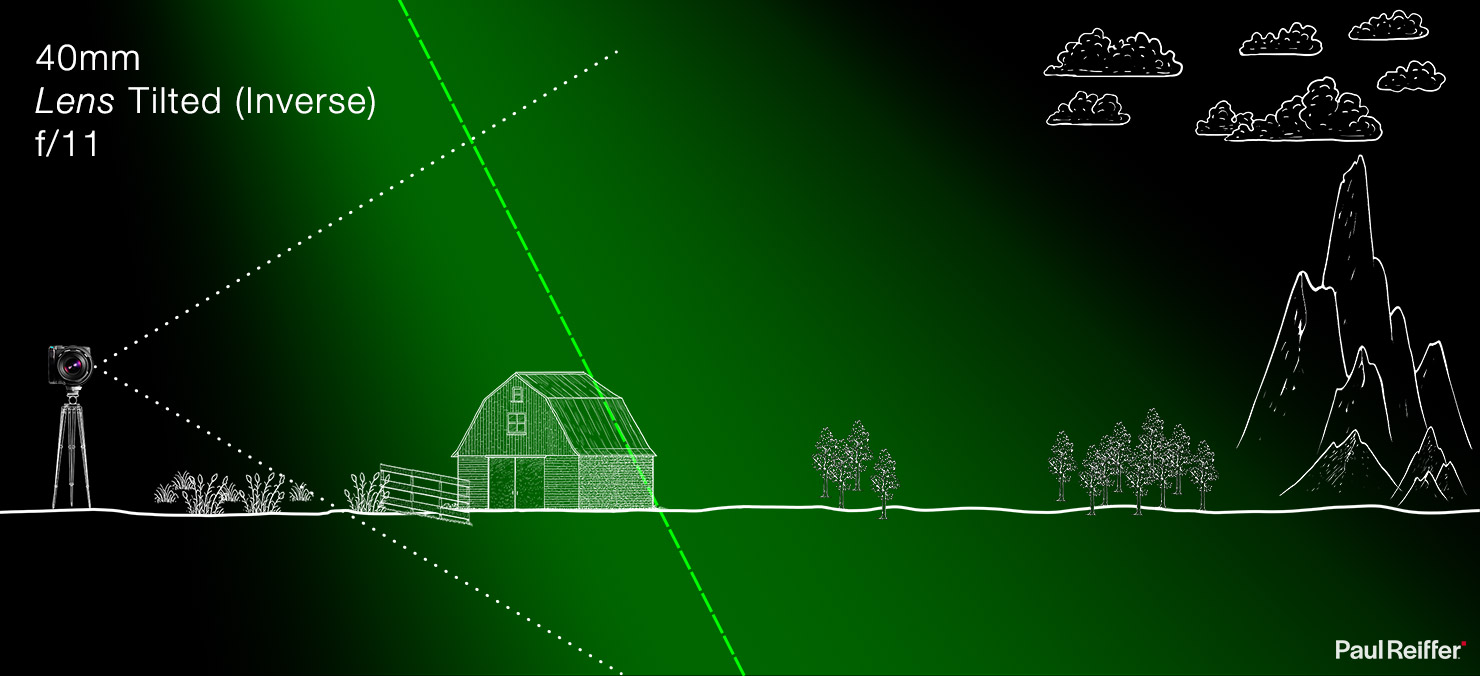

Only, instead of throwing the focal plane to catch everything from near and low to far and high, it’s flipped, catching only things high and near through to far and low. (ie: a very narrow band indeed).

With the more famous “T A Moulton Barn” across the street, I’d hoped (at least for once) to replicate the foggy scenes I’ve caught every now and then on my iPhone, when stood there one morning with my “big camera” instead.

Clearly, I did something bad the night before, as karma dictated I’d get low-lying, flat, dull, cloud instead – but still, it was enough to prove the point.

Dialling in some contradictory tilt, I could catch the difference between (effectively) leaning back, and pushing forward, with that same focal plane adjustment on the lens.

Pulling back, with positive tilt, we got that narrowing effect: What would normally be fully focused on an f/11 shot, was now thrown out.

The foreground in the left hand shot is completely out, as is the background. We’ve effectively narrowed the plane of focus by tilting it up towards the sky, away from the ground.

On the other hand, to the right, we have the same effect as at the John Moulton Homestead – with completely sharp foreground to background, at the same aperture and little diffraction, but tilting the lens down and towards the earth.

Of course, there are many landscape photographers, especially those who use technical cameras, who have been using this approach and type of lens for decades. Some of them have inspired me over the years – and while it’s a look that doesn’t necessarily work for some of the styles of images I capture, there are indeed times where I’ve been on a rooftop, or up-close with a subject, wishing I had access to one of these incredibly engineered lenses.

And now, it seems, I do.

The brand new Phase One 40mm XT Tilt lens from Rodenstock really does open up a new way of shooting on an already incredible camera system.

…and it’s almost like the sky over Jackson Hole agreed with me that morning too.

Reiffer’s final thoughts…

Regardless of your “big camera” type, you’ll likely find a tilt/shift lens option available to you in some form or other – so why not pick one up and give it a try?

You might actually find some of the older, more technical, kit is available at a lower cost too!

And for those who want to take a look at these subjects – or just love a great view – don’t be afraid to head into Jackson Hole airport for an incredible landing (and sad take-off, too).

Of course, as part of my never-ending mission to help educate the world, a few final thoughts.

- Frogs and earthworms are very good at camouflage in the dark, even with a headlamp…

- Takis “blue heat” should be classified as an offensive weapon, not a food product.

- A McDonalds Sausage & Egg McMuffin is not bettered when it’s put inside two pancakes?!

- Black Post-It notes seem like an amazing idea in the store – until you try to write on one and leave a note.

Oh well, we live and learn!

For those wanting more info, click through to the Phase One XT IQ4 Camera System and Phase One XT -Rodenstock Lens lineup.